EV batteries don’t have to rely on lithium forever. A sodium-ion electric vehicle battery stores energy using sodium ions instead of lithium ions. The basic idea feels familiar because the pack still powers an electric motor through the same kind of high-voltage system.

What’s new is timing. As of February 2026, CATL and automaker Changan have publicly tied sodium-ion cells to a mass-production passenger car program, with a mid-2026 market target. That matters because it moves sodium-ion from lab headlines to the messy world of real cars, warranties, and winter commutes.

This guide explains how sodium-ion EV batteries work, why companies care, where the tradeoffs still bite, and what buyers should watch over the next 1 to 3 years.

How a sodium-ion electric vehicle battery works, and what makes it different from lithium-ion

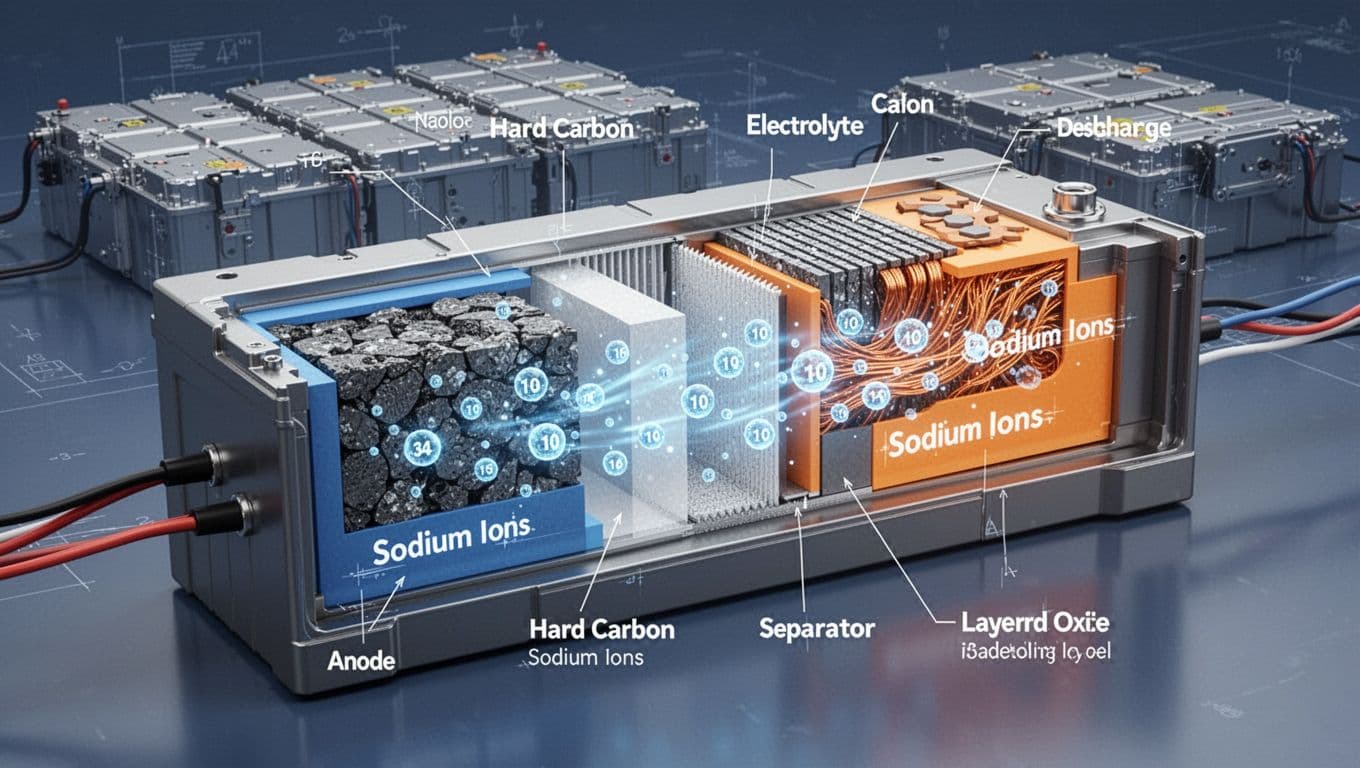

All rechargeable EV batteries work like a shuttle system. During charging, ions move in one direction through the electrolyte. During driving (discharge), they move back. Electrons take the long way around through the car’s wiring, which is what powers the motor.

In simple terms, the cathode and anode act like two parking lots. Charging “parks” ions on one side. Driving moves them back. The battery management system (BMS) watches voltage, temperature, and current, then limits power to protect the cells.

So why does swapping the ion matter? Because the ion affects how much energy you can store per pound, how fast reactions happen in cold weather, and how stable the materials stay under abuse. Those are not chemistry trivia points; they show up as range, winter performance, cost, and safety behavior.

For a recent, car-focused look at the first announced mass-production program, see InsideEVs coverage of CATL and Changan’s sodium-ion EV plans.

The simple chemistry: swapping lithium for sodium

Sodium is common. It’s widely available in basic minerals and industrial supply chains. Lithium is also abundant in the earth’s crust, but battery-grade lithium supply is more constrained and price swings can be sharp.

Most sodium-ion EV designs still look like modern lithium packs from the outside:

- Cells (prismatic, pouch, or cylindrical, depending on maker)

- Modules or direct cell mounting

- Pack enclosure, cooling, fuses, and contactors

- BMS software for safety and longevity

The key physical drawback is that sodium ions are larger than lithium ions. That larger size can reduce energy density because you often need more structure to host the ion. In practice, that can mean either less range for the same pack mass, or a heavier pack for the same range.

What “cell-to-pack” and pack design mean for range and price

When battery makers say “cell-to-pack,” they mean fewer layers between cells and the final pack. Less framing and fewer intermediate parts can improve space use, reduce assembly steps, and lower cost.

This matters more for sodium-ion because pack engineering can claw back some of what chemistry gives up. If cell-level energy density is lower, improving pack-level efficiency becomes a direct way to keep vehicle range reasonable.

Buyers should pay attention to pack-level numbers, not just cell headlines. A sodium cell can look “only OK” on paper, yet a well-designed pack can still fit a useful range target for city cars and commuter sedans.

The real-world benefits people care about: cost, cold weather, and safety

An EV driving in heavy snow, representing the kind of conditions where cold performance claims matter most.

Sodium-ion is getting attention for three practical reasons. First, it can reduce exposure to lithium pricing. Next, it can perform strongly in deep cold, where many EVs feel sluggish. Also, sodium-ion chemistries often aim for calmer failure modes under abuse.

It helps to compare sodium-ion to LFP (lithium iron phosphate), since LFP already targets affordability and safety. Sodium-ion competes in that same space, but with different supply inputs and different low-temperature behavior.

If you want a quick refresher on how mainstream packs differ today, this internal overview of BYD Blade Battery vs Tesla vs CATL gives useful context for how safety and range tradeoffs vary across popular lithium systems.

Lower material cost and fewer supply worries

Sodium-based supply chains can be less exposed to the bottlenecks that hit lithium, nickel, or cobalt. That doesn’t mean every sodium-ion pack will be cheap right away. Manufacturing scale, yields, and pack integration still set the real cost.

Still, the direction is clear: if the raw materials are cheaper and easier to source, entry EV pricing can become more stable. That’s important for automakers trying to build $25,000 to $35,000 EVs without betting the business on commodity swings.

A balanced comparison of sodium-ion versus lithium-ion for EV use cases appears in Bolt. Earth’s explainer on sodium-ion vs lithium-ion batteries for EVs.

Strong cold-weather performance that could change winter driving

Cold slows battery chemistry. It also limits charging power until the pack warms. Many LFP packs feel this sharply in freezing weather, especially on short trips.

Early 2026 reporting around CATL’s sodium-ion rollout points to unusually strong deep-cold behavior, including claims of minimal range loss around about -40°F (which equals -40°C) in some coverage. At a driver level, the “feel” you care about is simpler:

- More usable power right after a cold soak

- More consistent regen when the pack is cold

- Less range drop in extreme cold (not zero drop)

Cold claims only matter if the test method is clear. Ask whether results come from lab cells, pack testing, or a full vehicle drive cycle.

Safety advantages, and what “safer” really means in a crash or thermal event

“Safer” doesn’t mean “can’t catch fire.” Any high-energy pack can fail after severe damage or internal defects. The difference is how likely thermal runaway is, and how violently the system releases energy if it happens.

Sodium-ion makers often point to stronger tolerance in abuse tests and lower thermal runaway risk than many lithium chemistries. For buyers, the practical safety story is still about pack engineering: robust enclosures, thermal barriers, sensors, and software limits.

If an automaker shares safety results, look for standardized testing language, not only marketing terms. Real confidence comes from repeatable tests and conservative pack design.

What sodium-ion still struggles with: range, weight, and rollout speed

Battery crush testing concept, showing mechanical abuse without visible fire.

The biggest near-term limitation is energy density. If you store less energy per pound, you need more mass to hit the same miles. That can reduce efficiency, which then pushes you to add even more battery.

This is why sodium-ion is most likely to enter the market in segments that can accept a moderate range. City cars, short-commute sedans, delivery fleets, and cold-region vehicles all fit that pattern. On the other hand, long-range highway cruisers and heavy towing still favor higher-energy lithium chemistries.

A second limiter is ramp speed. Automakers validate packs for years, then validate them again in the real world. Even if cell factories are ready, vehicle programs still move at vehicle pace.

Energy density today, and why that can mean a heavier pack for the same miles

Public reporting around mass-production-ready sodium-ion cells has cited energy density up to about 175 Wh/kg. That’s a serious number for a new chemistry, but it still sits below the best high-nickel lithium cells used in long-range EVs.

Here’s the buyer takeaway. If two cars target the same range, the sodium-ion version may need a larger or heavier pack. That can affect:

- Highway efficiency

- Handling and braking feel (because the weight rises)

- Cargo or cabin packaging (if the pack grows)

In some designs, sodium-ion may land closer to LFP than many people expect. Still, premium range targets remain harder without more energy density gains.

Charging, cycle life, and the “good enough” threshold for daily driving

Charging speed is not one number. What matters is the full curve from 10 percent to 80 percent, and how often the pack can do that without heavy wear.

Some sodium-ion developers have discussed longer life than LFP in certain conditions, including claims of up to about twice LFP lifespan. Treat that as a company claim until independent, pack-level fleet data confirms it.

Meanwhile, research keeps pushing. For example, ScienceDaily summarized University of Surrey work on a “wet” sodium-ion material that boosted performance and stability in lab results, as described in this sodium-ion research report. That’s promising, but it’s not yet a car pack.

If you want an example of how owners think about battery aging and daily charging habits, this internal guide on Tesla battery pros and cons helps frame what “good enough” means in real ownership.

Why you won’t see it in every EV overnight

Even with strong headlines, sodium-ion has to earn trust at scale. Automakers will roll it out where the benefits are most obvious:

- Entry models where price matters most

- Cold-region trims where winter range complaints are common

- Fleets that value durability and predictable supply

CATL has also pointed to commercial vehicle timing, with passenger rollout first and buses or trucks later in 2026 for some programs. Even then, local standards and supply chains will decide where sodium-ion appears first.

Who is building sodium-ion EVs first, and what to watch next

A modern electric sedan concept on an urban street, similar to the kind of vehicle slated for early sodium-ion adoption.

As of February 2026, the market story is simple: one major battery supplier has put a date on a mass-production passenger car, and the rest of the industry is watching whether the numbers hold up outside controlled tests.

That makes the next 12 months unusually important. A chemistry shift only “counts” when it ships in volume, survives winter, and keeps warranty claims low.

The 2026 milestone: the first mass-production sodium-ion passenger EV

CATL and Changan have reported plans for a mass-production passenger EV using CATL’s sodium-ion batteries, tied to the Changan Nevo A06 (also referenced as Qiyuan A06), with market timing targeted for mid-2026. Public reporting has described a current range band over 400 km (about 250 miles), with higher projections depending on configuration and future versions.

Treat early range numbers carefully. They can depend on test cycles, tire choice, and software limits. Still, the key milestone is not a perfect range figure. It’s the move into a retail vehicle program with a schedule.

Signals that sodium-ion is moving fast: shipments, investment, and next-gen cells

CATL has said it began mass production of its sodium-ion battery line in late 2025, with installations in everyday vehicles discussed in early 2026 coverage. The company has also described large internal investment and broad testing.

At the same time, the industry keeps publishing aggressive ideas, including ultra-fast charging concepts. CleanTechnica’s overview of research directions gives a sense of the speculative space in this report on extremely fast charging sodium-ion concepts. That kind of work is interesting, but it’s far from a validated EV pack.

In other words, watch what ships, not just what publishes.

A quick buyer and investor checklist for separating real progress from hype

Use this short checklist when a brand announces a sodium-ion EV:

- Pack-level energy density (not just cell-level)

- Real-world highway range at US speeds, plus the test method

- Cold-weather details, including starting temperature and preconditioning rules

- Charging curve, especially 10 percent to 80 percent time and average power

- Safety test standards, not only “no fire” claims

- Warranty terms, including capacity retention language

- Production status, meaning orderable cars and confirmed delivery timing

For drivers who obsess over winter miles and trip planning, it also helps to understand the human side of range math. This internal guide on EV range anxiety explains why winter range feels unpredictable, even when nothing is wrong.

A sodium-ion electric vehicle battery won’t replace lithium everywhere soon. However, it can open doors for cheaper EVs, strong cold performance, and stable safety behavior in the segments that need those traits most.

Expect the first true production models to arrive in 2026, then broaden over the next 1 to 3 years as factories scale and pack designs mature. If you live in a cold area or you want a lower-cost EV that still feels reliable, sodium-ion models are worth watching this year.