You’re on a road trip, the battery’s low, and you’ve got 20 minutes to spare. You pull into a fast charger, plug in, and the car jumps from “almost empty” to “ready to drive” faster than most coffee stops. That experience feels almost like magic, but it’s mostly power electronics and careful control.

In plain terms, DC fast charging is fast because the station converts grid power into direct current (DC) and sends it straight to your battery. Your car still stays in charge, though. It constantly decides how much power it can safely accept.

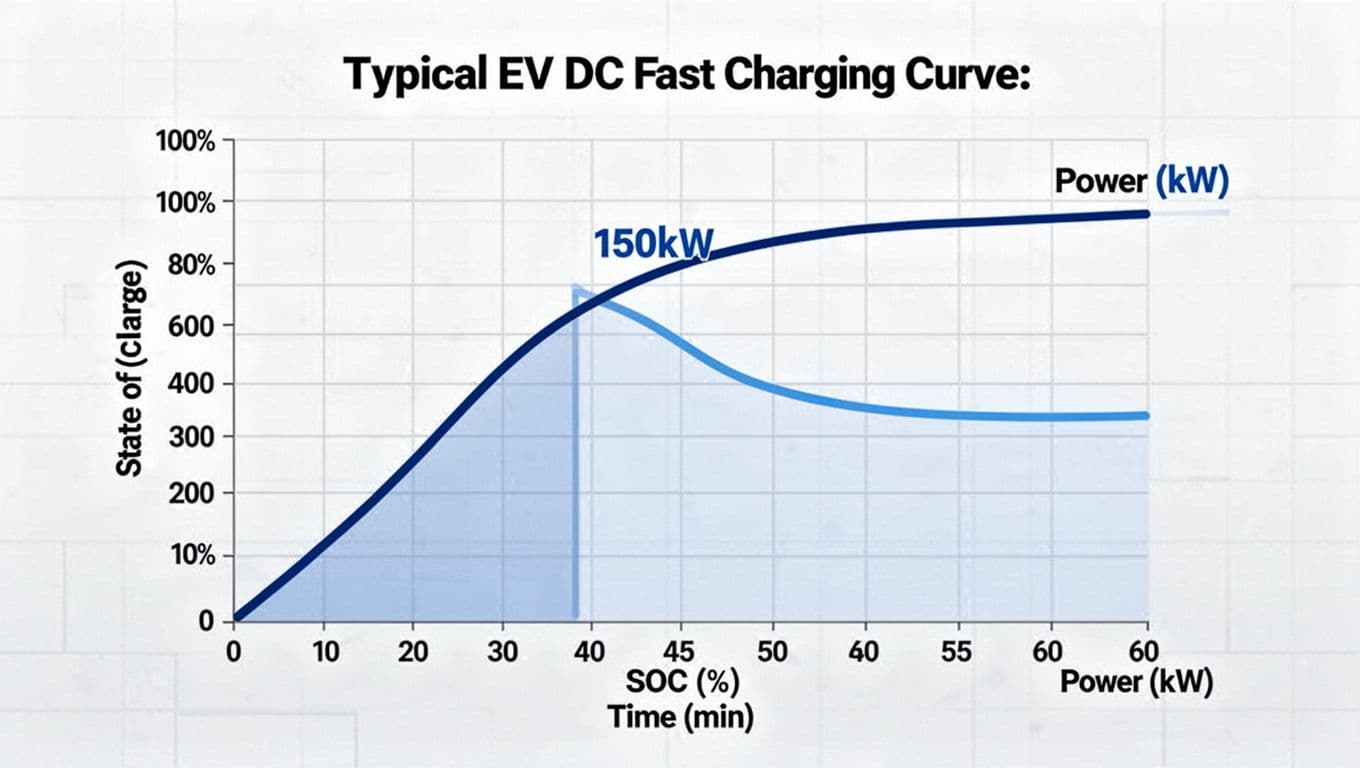

One more expectation helps: charging speed changes during the session. It usually starts strong, then slows near a higher state of charge. That taper isn’t a broken charger, it’s battery protection doing its job.

What makes a fast charger “fast” compared to home charging?

Home charging feels slow because it’s usually AC power that your car must convert. Fast charging feels quick because the heavy conversion work happens in the station, not in the car.

Here’s the simplest mental model:

- Level 1 and Level 2 charging normally supply AC (alternating current).

- DC fast charging supplies DC (direct current) directly to the battery.

A helpful analogy is water flow. Level 1 is like a small hose, Level 2 is a bigger hose, and DC fast charging is a wide pipe with pumps and sensors. Still, the pipe can’t force more water in than the tank safely allows.

To talk about speed, chargers use kW (kilowatts). Think of kW as the “rate” energy moves. Higher kW can add range faster, but only if your car can accept it.

For a grounded explanation of why DC stations charge faster than AC ones, see Advanced Energy’s overview of DC fast charging.

AC charging uses the car’s built-in converter, which limits speed

When you plug into Level 1 or Level 2, the car routes AC power through an onboard unit often called the onboard charger (it’s really an AC-to-DC converter). That device has a maximum rating, so it sets a ceiling on how fast AC charging can go.

That’s why charging at home or work often takes hours. Even if the wall power is available, your car’s onboard hardware still meters how much it can convert into DC for the battery. As a result, many drivers treat Level 2 like an “overnight refill” rather than a quick pit stop.

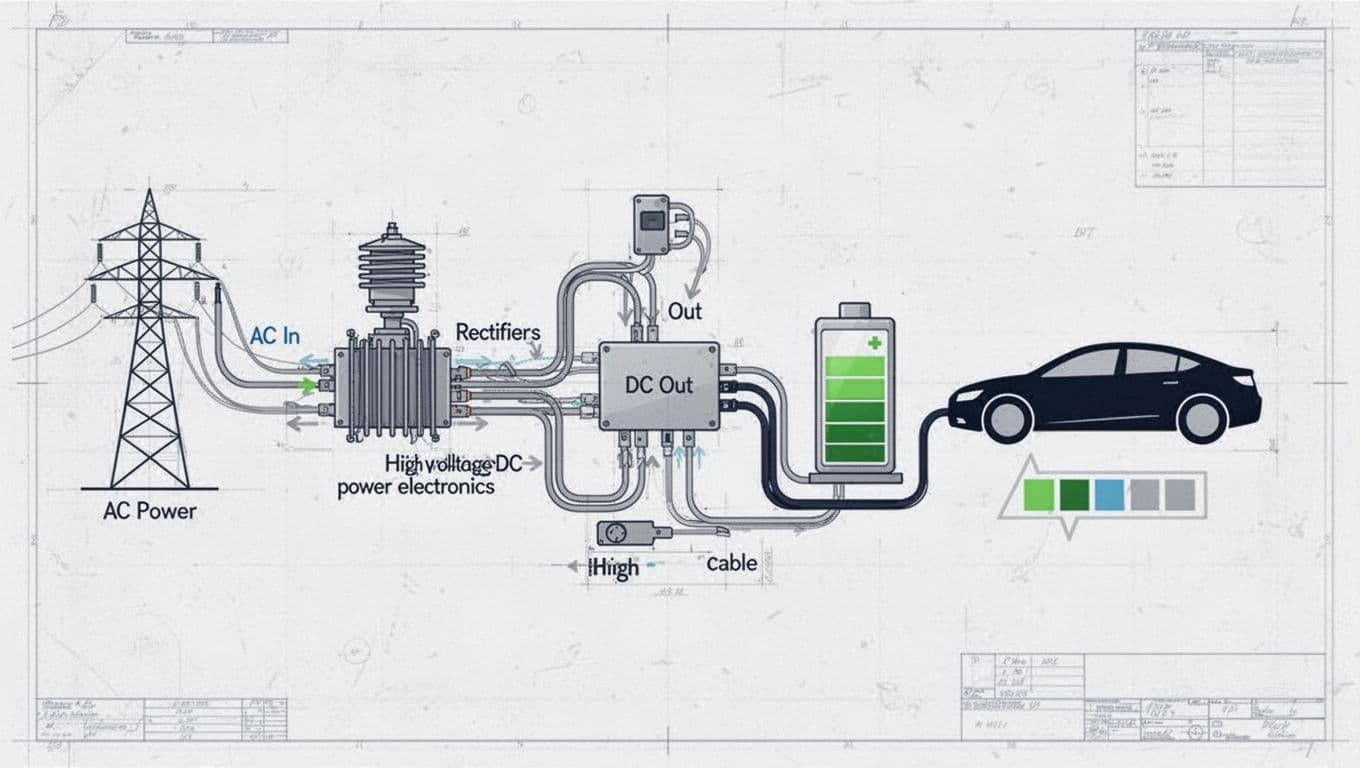

DC fast charging converts power at the station, then sends it straight to the battery

With DC fast charging, the station takes in AC from the grid and converts it using high-power electronics (rectifiers, filters, and controls). Then it sends controlled DC through a thick cable to your car.

That conversion equipment is large, expensive, and cooled for heat management. It’s also why DC fast chargers tend to sit at highway corridors, big retail sites, and fleet depots where the electrical service can support higher power.

Before the station delivers high power, the station and car must agree on safe limits. Even after that, the car can tell the station to reduce power at any moment. In other words, the station offers capability, but the car sets the rules.

What happens when you plug in, step by step

Typical highway DC fast charging setup with a tethered cable and status screen.

A DC fast charge session has a clear order. It feels instant to you, but several checks happen first because the power levels are high.

At a high level, most sessions look like this:

- You plug in and the connector seats fully.

- The connector locks, so it can’t be pulled under load.

- Payment or authorization completes (app, card, vehicle-to-charger account, or plug-and-charge where supported).

- The car and station exchange data, agreeing on voltage, current, and limits.

- Power ramps up, often in a smooth climb instead of a sudden jump.

- The station adjusts output continuously as the car requests changes.

- Charging stops when you end it, reach your target, or the car hits a limit.

- The connector unlocks, then you unplug.

Behind the scenes, DC sites also include utility-facing gear like switchgear and protective devices. If you’re curious what’s inside a site cabinet and why it’s not “just a plug,” Franklin Electric offers a clear look at key DC fast charging station components.

The charger and the car “talk” first, then charging ramps up

The “talk” is a short data session across the charging connection. The charger needs to know what your car can accept, and the car needs to confirm the charger can deliver stable power.

Your EV’s Battery Management System (BMS) is the safety boss here. It watches battery temperature, state of charge, cell balance, and overall pack health. If conditions aren’t right, it will request less power or refuse fast charging until the pack warms or cools.

That’s also why two identical cars can charge at different speeds on the same stall. A warmer pack, a lower state of charge, or different battery chemistry can change what the BMS allows.

Charging slows down on purpose as the battery fills up

Typical charging curve where power tapers as the battery fills.

Fast charging doesn’t stay fast all the way to 100 percent. Most EVs follow a charging curve: high power at a lower state of charge, then a controlled drop as the pack fills.

Two reasons drive that slowdown:

- Heat control: higher current makes more heat, and full batteries heat faster.

- Cell protection: pushing energy into near-full cells requires tighter control.

This is why drivers often hear “0 to 80 percent is the quick part.” The exact numbers vary, but the pattern is consistent across modern EVs.

If the last 20 percent feels slow, that’s normal. Your car is trading time for battery safety.

Connectors and power levels: what they mean for your real charging speed

Photo by Philippe WEICKMANN

People often focus on the number printed on the charger, like 150 kW or 350 kW. In practice, your charging speed depends on two ceilings:

- The charger’s maximum output

- Your car’s maximum DC intake

Your result is usually the lower of the two, and that’s before temperature and battery level reduce it further.

In the US, public DC fast charging is also growing fast. Recent tracking in early 2026 puts the country at roughly 68,000 public DC fast charging ports across about 14,600 locations. More ports help, but plug types still matter at the curb.

CCS, CHAdeMO, and NACS: the plug decides what you can use

North America has three connector families you’ll run into:

- CCS (Combined Charging System): Common on many non-Tesla EVs for years, still widely supported at existing DC sites.

- CHAdeMO: A legacy DC standard that’s fading in new deployments, but older stations may still have it.

- NACS (SAE J3400): Tesla’s connector style, now widely adopted and increasingly common on new vehicles and stations.

Because the plug is physical, you can’t “software update” your way into a different connector without an adapter. So it pays to check the station’s plug type in your route planner before you exit the highway. If you want a real-world example of where high-power plugs show up in dense areas, this guide to the fastest EV chargers in New York shows how connector access and stall power combine in practice.

A 350 kW charger won’t make every car charge at 350 kW

A stall labeled 350 kW is like a high-capacity pump. It offers headroom, but your car chooses how much to take. Several factors can lower power:

Battery level matters because power tapers higher up the pack. Temperature also matters because cold cells accept less current. Some sites share power between stalls, so a busy location can reduce what each car receives. Finally, not every EV supports high-voltage charging, so some models can’t use the highest output even under ideal conditions.

For typical public equipment ranges and what “DCFC” includes, Blink Charging’s explainer on what DC fast charging is matches what most drivers see at 50 kW, 150 kW, and higher-power stations.

As a practical example, many mid-size EVs can add enough energy for roughly 80 to 150 miles in about 20 to 30 minutes under good conditions. However, car model, weather, and starting percent can swing that a lot.

Safety, battery health, and how to charge faster in real life

DC fast charging pushes a lot of power through a connector you can hold in one hand. That only works because both the station and the car treat safety as a constant feedback loop, not a one-time check.

Modern stations monitor output many times per second. Meanwhile, the car watches the pack and adjusts its request. If anything looks off, the system slows down or stops.

For a simple definition of DC fast charging and how it differs from slower charging levels, Driivz provides a clear reference in its DC fast charging glossary entry.

Fast chargers have multiple layers of safety checks

Before high power flows, the system verifies grounding, connector seating, and secure locking. During charging, the station tracks voltage and current stability, and it checks for abnormal heat or fault conditions.

On the vehicle side, the BMS watches battery temperature and cell limits. If the pack is too cold, too hot, or near full, the car requests less power. That’s why “charger problems” are often “battery limits” in disguise.

If you ever see power drop suddenly, it’s usually one of three things: the pack warmed up, the pack got close to full, or the site is managing shared power. In all three cases, the system is acting to protect hardware.

Simple habits that can cut your charging time

A few habits improve results on almost any EV, without obsessing over brand or specs:

- Arrive low when practical (about 10 to 20 percent): The car can often accept higher power earlier in the session.

- Stop around 80 percent on road trips: The taper after that can be slow, so two shorter stops often beat one long one.

- Use battery preconditioning if your car supports it: Warming the pack before arrival can raise the accepted power, especially in winter.

- Match the charger to your car’s limits: If your car peaks at 150 kW, a 350 kW stall won’t hurt, but it may not save time.

- Use Level 2 for routine charging: DC fast charging is safe, but frequent use can add wear over time compared with slower charging.

The fastest session usually starts with a warm battery and ends before the last 20 percent.

Conclusion

Fast charging works because DC fast chargers convert grid AC into DC power and feed it straight to your battery. The car and charger communicate first, then the car’s BMS controls the rate minute by minute. Speed naturally tapers as the battery fills, since heat and cell limits tighten near the top. Before your next trip, check your connector type and your car’s maximum DC charging rate, then plan stops that keep you in the quick part of the curve.